Japanese Mess Kits

- Patrick Phillips

- Mar 22, 2024

- 9 min read

The Japanese military had used several varieties of mess kits ever since French, and later German military advisors brought their nations military cooking equipment to Japan. Although there are several distinct models of Japanese mess kit, they were generally referred to simply as Hango (飯盒), or rice cooker. This article won’t go into great detail about these early mess kit designs but will instead cover the most common Japanese mess kits encountered during the Second World War. Included at the end of this article are also accessories such as wicker bento boxes, fuel cans, and chopsticks. While not mess kits themselves, they are important elements in the story of mess kit development and military eating in the Imperial Japanese army.

Sho-5

In 1930 the Imperial Japanese army received an entire facelift. New, modern equipment and uniforms were introduced, including tropical gear. Included with the introduction of this new equipment was the 1930 mess kit or Sho-5 (Showa Year 5). This new mess kit was made of pressed aluminum and featured a double pot arrangement with steel hinged carry and cooking handles on both pots, plus an aluminum inner tray and lid. One pot was slightly smaller and was nested inside the larger pot for storage. The tray sat inside the inner pot, and the lid fit over the top, closing the entire kit. One major drawback to this design was in the lid. Both sides of the kidney shaped lid were notched in order to fit over the studs of the carry handle when stored. This essentially made the lid useless as a cooking or eating item. These mess kits are extremely rare and were not common during World War Two; however, it is important to include here to illustrate where later Japanese mess kits developed from.

Type 92

Developed in 1932, the Type 92 mess kit is a modification of the earlier Sho-5 model. The Type 92 still maintains the basic double pot with hinged carry handles, tray, and lid arrangement, as well as the double carry handles of the previous model. Based on experiences in the field, some minor and major changes were made to improve the Japanese soldiers mess kit. The most important change was made to the lid. Now, instead of the lid being notched to accommodate the carry handle studs, it was solid around its entire perimeter. This now allowed it to be used as an extra food tray or for soup. This change required that the top of the inner pot should be made taller, in order to raise the rim of the lid above the carry handle studs.

In keeping with the previous model, the inner tray was sized to accommodate one meal worth of rice, making for easy cooking and rationing of food. The sides of both pots are indented with rectangular divots, one low on the pot, and one higher up. These indentions indicate serving sizes. The lower mark was for one meal, and the higher for two meals. When used in the field, it was intended that one soldier would cook four meals of rice using both pots, while his squad mates would use their mess kits to cook soup or side dishes. The food would then be divided up between squad members.

One interesting design element of the Type 92 is its ability to stack pots on top of each other for easier handing while in the field. Once rice or soup was done cooking, the soldier could take the inner tray and place it inside the larger outer pot. The smaller inner pot could then be nested inside the tray, and the lid placed on top of the upper pot. This feature allowed a soldier to carry four meals of food easily without having to worry about spilling any.

The Sho-5 and Type 32 mess kits were relatively short lived. Years of ever-increasing conflict on mainland China, and a looming war with the Allied powers forced the Japanese to begin conserving war material and new designs were introduced in order to facilitate this. During this period, it was decided that the Type 92 mess kit was too expensive to produce and used way too much aluminum. It was essentially providing two mess kits to every soldier. In 1939 the Sho-5 and Type 92 were phased out of service and replaced with a more simplified design.

Type “Ro”

In 1939 Japan was in the midst of a material squeeze and military leadership sought ways to conserve critical aluminum and use recycled aluminum for new products. A new mess kit was introduced that was vastly simplified from the previous Sho-5 and Type 92 and used far less aluminum. This new mess kit was known as the Type Ro and could be manufactured from recycled aluminum.

The new design did away with the double pot and hinged carry handle design. It now featured a single large pot but retained the same basic kidney shape as previous mess kits. It also continued to feature the meal serving indents on the side of the pot, as well as the single serving inner tray. However, the depth of the lid doubled in size, making for a more suitable soup bowl. The carry handle was now a single steel wire that still allowed the soldier to hang the pot over a cookfire.

The Type Ro mess kit was the most common issued to Japanese soldiers during the Second World War and continues to be the most common in collections today. Although they were issued in the classic Japanese army brown/green paint, they quickly blackened from the soot of cookfires. Type Ro mess kits were manufactured by several companies within Japan and are marked on the upper portion of the pot

with the square Japanese character ロ, for “Ro”, next to the maker and date stamps. These mess kits were marked with army acceptance and year stamps in white paint on the bottom of the pot. These markings are often worn away from use and storage or are burned away during cooking.

Last Ditch Mess Kits

In late 1944 Japan was in a critical shortage of war material and production capabilities. Japan had to import almost all of its aluminum and its reserves of scrap aluminum were drying up. Shipping was decimated by allied submarines and aircraft, placing a strangle hold on the country. American air power and strategic bombing campaigns reduced Japanese factories and cities to rubble and ash. Not only were the Japanese short on raw material, but they were also losing the industry required to manufacture military items.

At this time, a “last ditch” mess kit was introduced. Instead of being pressed, it was now made entirely of cast aluminum. These last-ditch mess kits did away with the inner tray, and now only have a shallow lid and a thin steel carry handle. These late war mess kits are quite crude and still show the rough sand cast texture on the inside of the pot and lid. Interestingly, these mess kits still bear makers marks on the bottom of the pot, as well as the serving indicators. Instead of being pressed into the side of the pot as indentions, the serving marks are now cast as raised bumps on the interior of the pot.

Like previous generations of mess kits, the late war models still retain a strap of aluminum riveted to the outside of the pot for carrying on a pack. This strap is also marked with a somewhat crudely stamped five-pointed army star. The lids of last-ditch mess kits also bear a large, machined area

approximately 2 ½ inches (64mm) in diameter. This was most likely the only machine operation performed on these mess kits and was done to remove the remaining aluminum stud left over from the casting process.

Officer Mess Kits

For many years there has been confusion related to the mess kits used by the officer corps and non-commissioned officers (NCOs). Like almost all armies, Japanese officers take on the responsibility of administrative functions and planning, as well as leading troops in the field. Their positions and status as officers often exempted them from most manual labor, including cooking their own meals. However, this exemption was in contrast to their leadership responsibilities. Although an officer may not be digging a ditch, the success or failure of the units under their command was placed on their shoulders.

Officers were required to purchase much of their own equipment. Officers had a short list of approved versions of equipment that they were authorized to use, leading to some variation in equipment encountered as well as high quality privately purchased accessories.

All models of Japanese officer mess kit are short, with a rectangular shape. Early models are quite long with a shallow lid and inner tray. These early mess kits often lack a carry handle. Since officers were often not expected to cook their meals, these mess kits served more as a bento box. Meals would be cooked by enlisted men, and officer mess kits filled with that meals ration and taken to the officer. Later models of the Japanese officer mess kit are slightly shorter and taller, but still retain the same basic rectangular shape. These later models commonly have wire carry handles similar to the enlisted mans mess kit. Some models have carry handles that can slip downward to make carrying in a pack easier.

Non-commissioned officers (NCOs) were senior enlisted men. Not much information exists about the exact roles and responsibilities of Japanese army NCOs, but one can surmise that they are similar in function to those of NCOs in western armies, but to a lesser extent. Being enlisted men, NCOs were not required to purchase equipment and were instead issued the standard army hango. The smaller rectangular mess kits with carry handles encountered by collectors have often been incorrectly referred to as “NCO” mess kits.

Accessories

While not technically mess kits, there were several accessories used by officers and enlisted men to either facilitate the carrying, cooking, eating, or storing food. Wicker boxes were used in tropical climates to carry cooked rice while on the march or patrol. The humid environments of the Pacific would cause cooked rice to spoil quickly in a mess kit. The wicker boxes allowed for air flow and would thus extend the freshness of the cooked rice. Pickled plums were often added to the center of a rice ration. The acidity of the plum would extend the freshness of the rice and deter bacterial growth. A cooked rice ration would be packed into the basket and then carried in a small net. This arrangement could then be strapped to the top of a soldier’s ruck sack or carried within his bread bag.

Small, round aluminum cans have also been encountered. These are referred to in Japanese texts as “Officer side dish containers”. Measuring 3 7/8th inches (98mm) in diameter and 1 inch (25mm) in depth. These small cans feature a rubber inner gasket around the inner perimeter of the lid and are fastened closed by three steel snaps with wood rollers.

The intense cold of Chinese winters forced the Japanese army to develop specialized equipment for keeping food from freezing solid while on the move. Fur lined pouches were developed for both the mess kit and canteen. These pouches were designed to insulate food and water against freezing temperatures and were widely used in China, Manchuria, and Korea.

Cooking

Mess kits were designed to be hung above a cook fire by their wire handles for cooking. Often, several mess kits were suspended together on a stick and cooked at the same time. When making cookfires was not practical, two types of cooking fuel were issued.

The first, and most common type of cooker was canned gelled cooking fuel. This can contained a jellied cooking fuel that would allow a soldier to cook two mess kits at one time. Instructions were included on the can label illustrating how to cook with the fuel. These cans are somewhat similar to American jelled cooking cans, but are shorter, and slightly larger in diameter. These cans must be opened by a can opener and are not intended to be reusable.

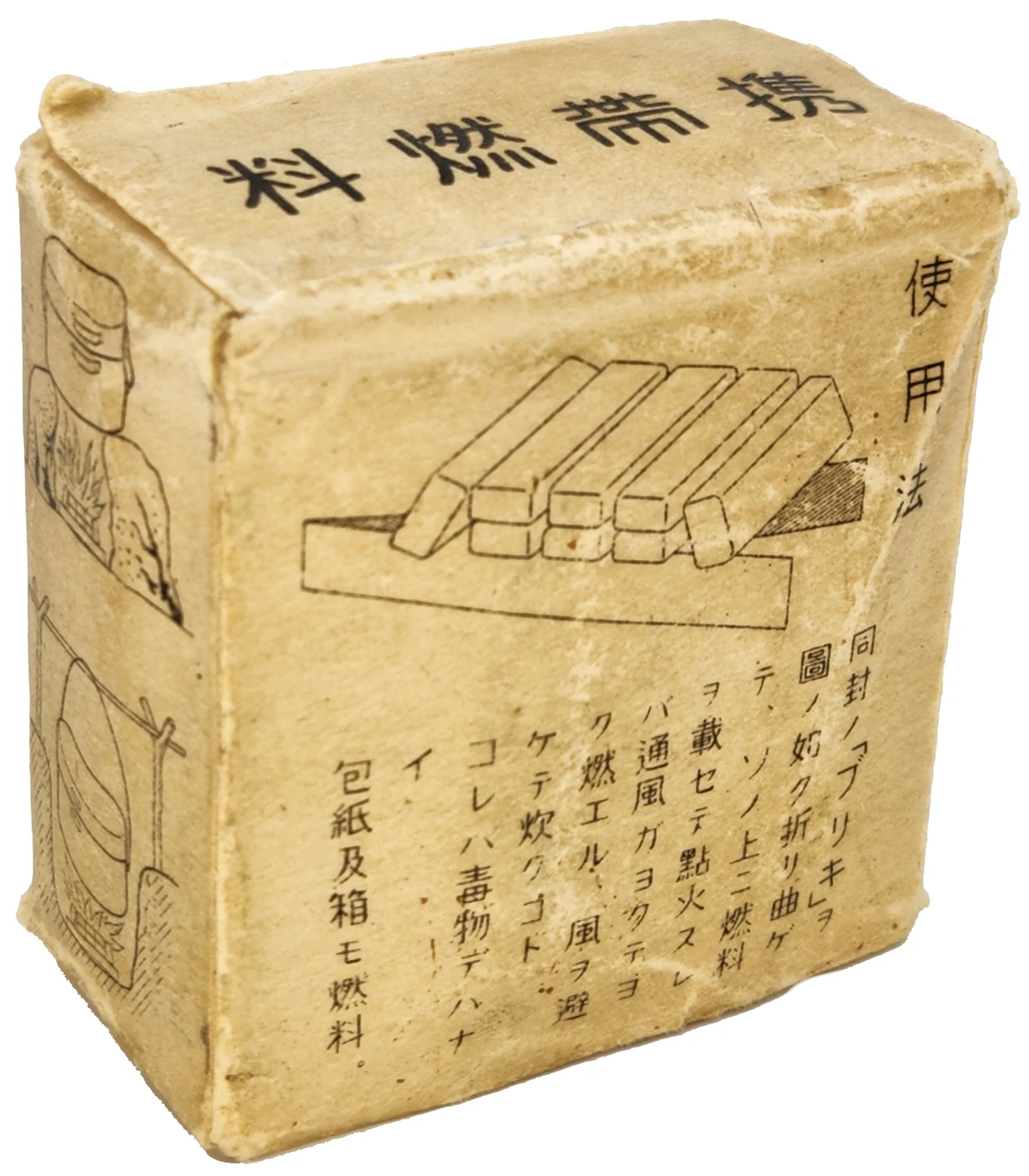

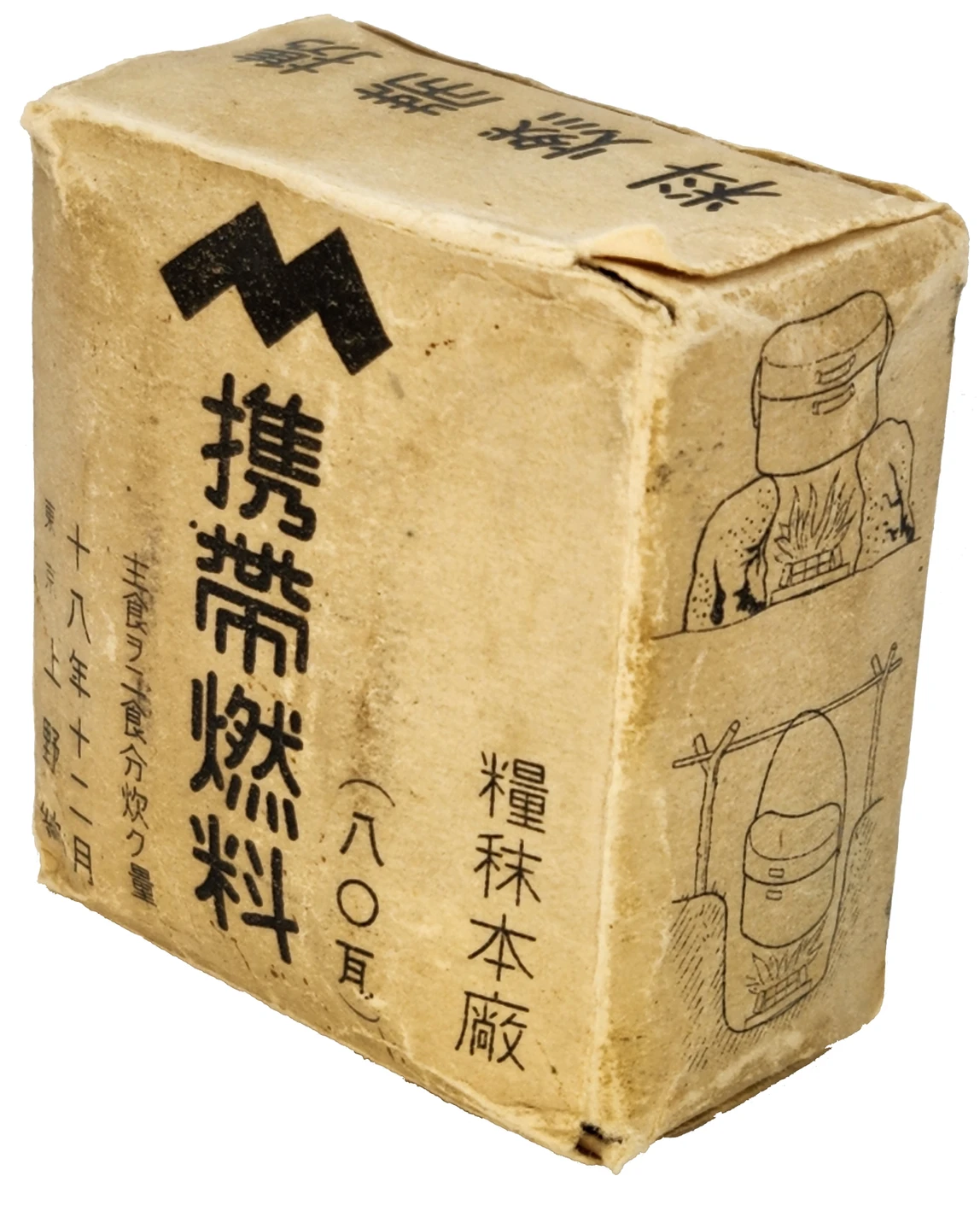

The second type of cooking fuel are solid flammable tablets. These rectangular tablets are essentially the same as German Esbit fuel tabs used by the Wehrmacht. Sixteen fuel tablets are wrapped in a dark wax paper and packed into a beige wax paper box. Included in the box is a thin strip of flexible aluminum to allow for the burning of the fuel tablets. Like the cooking cans, the boxes contain cooking instructions, but are intended to only cook a single mess kit. These tablets are extremely rare, and not often seen, even in Japanese texts.

Chopsticks

While forks and spoons were used to some extent by Japanese soldiers and officers, most meals were consumed with chopsticks. Soups were often drunk directly from the cooking pot or bowl. Practically all Japanese soldiers carried a personal set of chopsticks in their pack or bread bag. These sets of chopsticks were often stored in a wooden box with a sliding cover, or in a sleeve made of other materials. Disposable chopsticks were also issued.